The Whole Picture

A word’s meaning evolves over a long period of time. Tracing its roots can be revealing. Seemingly disparate words often share common roots and import. Such is the case with synapse, yoga, algebra, and art. Each in its own way denotes joining things together to create greater wholes.

Synapse

It’s apt to start with this biological term as millions of mine and yours are sparking now as I write and you read! A synapse is like a junction. It facilitates the exchange of

electrical signals from nerve cells via interconnected circuits throughout the central nervous syste

electrical signals from nerve cells via interconnected circuits throughout the central nervous syste m. Young children have some 1,000 trillion in their brains. As we age, this declines. Most adults have between 100 and 500 trillion synapses. Through this synaptic activity, biological impulse is magically transmuted into perception and cognition.

m. Young children have some 1,000 trillion in their brains. As we age, this declines. Most adults have between 100 and 500 trillion synapses. Through this synaptic activity, biological impulse is magically transmuted into perception and cognition.The term is derived from the ancient Greek synapsis meaning co

njunction. It was first coined in the late nineteenth century by the British physiologist Sir Michael Foster. It gained wider exposure through his student, Sir Charles Sherringon, who won the 1932 Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology.Apse is a related architectural term. Both stem from haptein, which originally meant joining arcs to form a circle, especially in reference to wheel making.

njunction. It was first coined in the late nineteenth century by the British physiologist Sir Michael Foster. It gained wider exposure through his student, Sir Charles Sherringon, who won the 1932 Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology.Apse is a related architectural term. Both stem from haptein, which originally meant joining arcs to form a circle, especially in reference to wheel making. Yoga

Yoga is an ancient Indian practice, dating back to 2500 BCE, possibly even earlier. Its name derives from the Sanskrit yuga

, which means to join, or yoke together. A yoke is a wooden bar that fits over the necks of animals to pull a cart or plow. Generally associated with servitude, the yoke once had a more positive social meaning. In Old English, for example, it meant a bond of partnership or cooperation. The goal of yoga is to yoke our temporal being to the divine imperative, just as the oxen is yoked to the higher purpose of drawing the plow.

, which means to join, or yoke together. A yoke is a wooden bar that fits over the necks of animals to pull a cart or plow. Generally associated with servitude, the yoke once had a more positive social meaning. In Old English, for example, it meant a bond of partnership or cooperation. The goal of yoga is to yoke our temporal being to the divine imperative, just as the oxen is yoked to the higher purpose of drawing the plow.Algebra

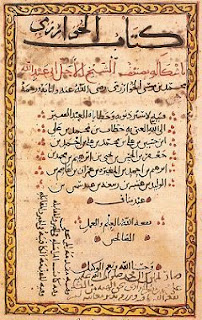

Algebra is concerned with that branch of mathematics in which symbols, usually letters of the alphabet, are used to represent unknown numbers. In 830 CE, Al’Khwarizmi wrote Hisab al-jabr w’al-muqabala, or The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing, from whence algebra got its name. In Arabic, Al-Jabr means the reunion of broken parts. Al’Khwarizmi also developed the concept of algorithms so crucial to computational technologies today. In an earlier post I discuss how Fibonacci introduced the term zero to the West. His source was Al’Khwarizmi. Al’Khwarizmi also led a team of seventy geographers to calculate the earth’s circumference and develop a world map.

This idea of measured calculation is also expressed by the term ratiocinate, to reason methodically with precise logic. Its root is the Latin ra, which means to fit together. Ra in Latin is actually a transposed Ar. We will come back to Ar below. This transposition between letter and sound, called metathesis, is common in many languages. Of course, there’s always the danger of too much adherence to strict reason and logic. Shaw describes one his characters in 'Androcles and the Lion' as an “inveterate Roman Rationalist, always discarding the irrational real thing for the unreal but ratiocinable postulate".

Art

The Latin root ar means to join together. Related terms include arm, artery, are, article, and articulate. Art is another related term. However, in its definitions there aren’t any related to the idea of joining things together. It’s actually there but hidden. Between the Middle Ages and Renaissance, education was largely the Church’s purview. It was the only institutional steward of knowledge in the West after the fall of the Roman Empire. It took several centuries to rebuild civil authority and society. During this period, the Church continued to use Latin, the empire’s lingua franca, throughout Europe and the British Isles. It also established universities in the larger cities.

The curriculum then consisted of several required ‘branches’ of learning (called the Trivium and Quadrivium respectively). These included mathematics, rhetoric, music, and philosophy. A student who successfully completed the entire course graduated as a Master of the Arts. One could have easily called him or her Master of Joinery. For that is essentially what they did. They integrated the knowledge gained in each branch within one larger conceptual frame and worldview. The value of artem - this ability to effectively join things together - was widely understood and appreciated, whether in producing good walls, wheels, and scholars। It takes skill and creativity to build something whole and enduring from smaller bits, whether these are stone, wood, or ideas. True then and now.

This calls to mind those master artisans who construct works of great beauty and utility by joining natural elements together. For example, the stonewall mason able to fit rough stone to stone, without cement, so that their walls stand for centuries। Or, consider for example, a furniture wright who joins disparate wood pieces together without nails, so that the piece serves for ages too.

The Greater Conjunctio

Alchemy is concerned with nothing less than the union of opposites, the squaring of the circle, and the rebirth of the phoenix. In its final stage, called the greater conjunctio, all one-sidedness is rectified. Alchemists also called this stage, zygon, which is ancient Greek for the even older Sanskrit yuga, which means, of course, joining. In The Act Of Creation (1964), Arthur Koestler provides a tour de force analysis of the creative process within the arts and sciences. His principle finding is that all acts of creation involve the novel intersection of idioms, concepts, processes, and materials. He developed a conceptual framework called the bisociative pattern of creative synthesis to describe this process.

One of his many examples involves Guttenberg’s quest to create what didn’t exist

and had no name। After great challenge and set back, Guttenberg wrote in his journal: What am I to do? I do not know: but I know what I want to do: I wish to manifold the Bible. I wish to have copies ready for the pilgrimage . . .[1964:122]. In his fervent and fertile inventiveness, and through much trial and error, Guttenberg ultimately and ingeniously married together three entirely different manufacturing processes – the manual hand printing of pictures from wood blocks, the metal die casting of standardized coins, and the wine press.

and had no name। After great challenge and set back, Guttenberg wrote in his journal: What am I to do? I do not know: but I know what I want to do: I wish to manifold the Bible. I wish to have copies ready for the pilgrimage . . .[1964:122]. In his fervent and fertile inventiveness, and through much trial and error, Guttenberg ultimately and ingeniously married together three entirely different manufacturing processes – the manual hand printing of pictures from wood blocks, the metal die casting of standardized coins, and the wine press.This is bisociation, or Ar, in action.I call yoga, algebra, and art the primary imaginal joints। Each joins things together in its own way. The symbolism of their colors further underscores this, yellow [yoga] for spirit and faith, blue [algebra] for science and reason, and red [art] for creativity and feeling.

E.O. Wilson, the biologist, foresaw the potential integration of the sciences and humanities. In 1998, he introduced the term consilience to describe this “jumping together of knowledge... across disciplines to create a common groundwork for explanation." Seven years later, Bill Gates, a Microsoft founder, refers to consilience in a special essay he wrote for Business Week: These technologies promote "consilience" -- literally, the "jumping together" of knowledge from different disciplines. They help people combine their own ideas with at least some existing knowledge far more efficiently than was previously possible.

Fractal Logic

Tellingly, Mandelbrot derived the term fractal from the Latin fractus for broken, uneven. The fractal is another good term for these times. It’s an irregular or fragmented geometric shape that can be repeatedly subdivided into parts, each a smaller copy of the whole. Fractals are used in computer modeling of natural structures that do not have simple geometric shapes, for example, clouds, mountainous landscapes, and coastlines. They’re used to digitally reproduce complex natural shapes like clouds, coastlines, and mountain ranges. Digital artists also use them to create luminous works of computer art.